My name is Mary Fields. I was born into slavery, but I’m a free woman now—and when I say “free” I mean it in every sense of the word. I do what I want—I smoke cigars, drink whiskey, and fight better than any man in Montana Territory, white or colored.

Some say I have no rights because I’m colored—an ex-slave. But even white women don’t have the right to follow my habits. Being colored is only a small sliver of it—being a woman is the main part that holds us back. And that is just what I intend to change. They call me a pioneer for women’s rights, but shouldn’t every person have the opportunity to live their life the way they choose…including women?

I’ve held off wolves, carried the mail, and I love baseball. I’ve helped open and run a mission for young Crow women, and I’ve gotten falling-down drunk. I can hitch a team faster and better than any man alive. I’ve been accused of having “crass behavior” more times than I can count. When they see me coming, they shake their heads and mutter, “One stagecoach, one shotgun, and two hundred pounds of bad attitude.”

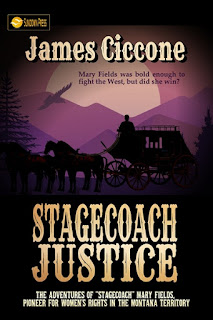

They aren’t wrong. I’m “Stagecoach” Mary Fields, and I’ve lived my life the way I wanted to. All women should be able to do the same. I’m a fighter, and this is my lifelong battle—I will do whatever it takes to bring equality to this old world. This is the story of how I lived and died—and brought my own brand of STAGECOACH JUSTICE to the wild Montana Territory…

EXCERPT

I could brawl, smoke, curse, drink whiskey, hitch a team of horses, fend off wolves, bandits and robbers, shoot a shotgun, draw a pistol, tend to the sick and needy, and do a whole host of other things better than any man, white or colored. Why should anyone be allowed to pretend other-wise? The rancher was only the latest man to see things my way. The nasty disposition had everything to do with the trouble I had come through in life.

I respected Mr. Lincoln, and I had a habit of cursing and insisting on equal treatment for women in public. I won-dered if any of the ranchers in Cascade were Republicans and felt the same way. I doubted it. They were probably Copperheads. Either way, I was sure they would have no problem respecting a punch in the nose.

By the age of thirty-two, I was no longer regarded as mere inventory on a slave master’s ledger in Hickman Coun-ty, Tennessee. Mr. Lincoln had seen to that. Having been born into slavery at or near 1832, 1833 or 1834, there was no clear record of my birth other than a journal entry listing me as estate property. So, I could not have said that bad luck began for me at birth, because I had no idea when I was born. And there were no records to help me figure it out ei-ther, no photographs, no certificates, no writings of any kind, nothing. My suspicion, though, was that bad luck had begun for me on the day I was born into slavery.

I had no experience with any other institution or lifestyle other than the one that had given me bad luck from the start, but I was determined to try to change. Thanks to Mr. Lincoln, I was finally free, free and flat broke.